1. Systems Theory.

“Obvious, yet subversive…an old way of seeing, yet somehow new…comforting, in that the solutions are in our hands. Disturbing, because we must do things, or at least see things and think about things in a different way…”

~ Donella H. Meadows, environmental scientist and systems theorist.

If you wish to tackle the world’s hardest problems, at first glance, you may believe yourself to be spoiled for choice, with all manner of problems in all facets of life, many of them indeed large and genuinely threatening. But we would be getting ahead of ourselves by asking the question of ‘which problems to tackle’. Indeed, in this approach, we learn the tools for tackling issues, the how, before we identify problems. If you find this a tad counterintuitive, there’s a reason why. Faced with combatting global catastrophe this century, should humanity approach our problems as a suite of different crises, or will we be better off understanding our many problems as expressions of a root crisis, something underlying multiple crises, something that speaks a more universal language? What we can know for certain is that the latter approach doesn’t appear to be used often. In the UK, it is around 14 years of age, with the selection of our GCSE subjects, that we first specialise. How much reasoned thought and reflection on the nature of the future goes into those first choices? A few years down the line, we further specialise. We decide if we will stay on for our masters, or our doctorate. In doing so, we drill down an ever-narrowing domain of knowledge, which enlightens everything behind it. This is called ‘reductionism’, and it has long been the dominating approach to science, which we can define as humanity’s collective effort to unmask ‘external ignorance’. Reductionism is a theory that phenomena in reality can be explained by analysing and understanding simpler, more fundamental components or principles. We break down concepts into their building blocks. But, in doing so, what do we actually learn?

When we take a stroll across a university campus, wander through its grand and ancient halls, and consider all of the different disciplines, all the information held in the hallowed halls, along with how many collective millions of years humanity has dedicated to their study, it all begs the question: why do so many things still go wrong? Why is life on earth best characterised by struggle and toil at mass scale, given how deep an understanding we have of reality? We can browse the unfathomable numbers for quantities of material we produce as a planet, billions upon billions of tonnes of everything. We live in an age of superabundance, which often goes unconsidered by Westerners. Given these numbers, why do we not live in some kind of society with a massive middle class, where most of the population lives comfortably, perhaps albeit under fabulously rich politicians and a very sizable, but less top-heavy upper class? Or at least, why aren’t things cleaner, safer, or simply better? Beyond a shared struggle, why do the actions of the powerful often seem to stray into unabashed contempt? As the HS2 project wraps up in the UK, totalling north of £100 billion for a trainline to Birmingham, all to shave half-an-hour off the current travel time; as apparently monumental crises, from climate to demographic haunt our children’s lives, why is it that money is spent so poorly? Despite the professionals involved all having such in-depth knowledge on their specialised piece of any project, why do so many projects go south? To characterise Gen Z life, we are thrusted into the world with a given knowledgebase and skillset, only to find a world that is still unfamiliar. Growing up in the liberal West, it doesn’t take too many car-journey radios and TV encounters before you begin to clock on that adults love to argue. It would perhaps then be easy to exclaim: “reductionism is failing us!” — but is that true? After all, despite its problems, we nevertheless live in the sci-fi present. Relative to other societies, we enjoy safe and quiet communities, a vast array of food and materials available at all price points, clean public amenities and some social amenities, public transport, and so on. Virtually all of this was made possible by the reductionist approach to knowledge acquisition. So instead, is it perhaps the case that in our times, we’re instead hitting some kind of ceiling? As we will explore in Chapter 2, these’ days, the quest to observe ever smaller pieces of reality has become a war of attrition, and the popular discussion more-often concerns theoretical physics.

What we can know for certain is that we live in an age of new problems. As discussed, our definition of ‘Capitalist’ has somewhat broken down in recent times. Living in the sci-fi present, we can point to a group of professionals with access and hence potential to charge consequential systems in society: central bankers, corporate bankers, politicians, ‘politically active’ ultra-high-net-worth individuals, lobbyists, and so on. As an increasingly distrustful and angry population of everyone else, we ultimately rely on this consequential class of individuals, through the actions of their employees, to uphold the structure of society and maintain the peace through the operation of the systems they control. In doing so, while the social contract is muddied by limited liability, we nevertheless task these individuals with solving new problems, which are often the manifestations of the unprecedented times that we live in. For these individuals, their survival needs are met, along with a lot their ‘higher needs’, such as family and security, by virtue of their high salaries and the benefits afforded to them by their network of class constituents. They do this in return for wage and capital. They sit upon massive wealth’s of knowledge that have been accumulated, studied, recontextualised, applied, and recorded over centuries by many of the brightest people to grace the earth, which is executed through a team of professionals to harness their collective intelligence. And yet, we still struggle greatly to tackle these new problems. We spend years of our lives coming to understand all the components of said problem, but in the real world, they still go unsolved. We can take global hunger as an example. Gabriel Ferrero, Chair of the Committee on World Food Security, in 2022 said: “That close to a billion people go hungry is an indictment on us all”. And indeed, we produce enough food to feed 1.5x the global population, there is objectively enough food for everyone, and yet, a billion go hungry, and an entire third of all the food produced goes to waste, 1.3 billion tonnes of perfectly good food worth almost a trillion dollars [18]. So, what is the problem? According to Ferrero: “the problem is our systems — the way we produce, harvest, transport, process, market, and consume food” [19]. Herein lies a common theme with the new problems of the present, and the answer to why a reductionist approach doesn’t solve them. These problems are products of how all the pieces come together at larger scales, going on to exhibit unintended and unwanted behaviours that affect us. We already know all the pieces, but they come together and conspire in unknown and mysterious ways as things continue to get bigger, more advanced, and more interconnected. In the context of an increasingly globalised world, where massive international companies and globe-spanning networks subsume ever larger populations of people into their sphere of influence, unintended behaviours at this level cause humanity discomfort, hardship, and death on large scales.

There are other approaches to knowledge acquisition, other directions to walk in. In the 2020s, as more of humanity comes to sigh, and begin crawling in new directions through the dark, it should hence come as no surprise that the discipline of ‘systems thinking’ is growing in prominence. Systems thinking is a mode of conceptualisation, or a ‘way of thinking’. Compared to reductionist thinking, we can understand systems thinking as a sort of opposite; a holistic approach to understanding reality. I began this chapter with a quote from Donella Meadows, who before her untimely death in 2001 was a Harvard-educated, highly respected scholar and educator. She first saw acclaim for her book ‘Limits to Growth’ in 1972, which famously predicted environmental and economic collapse within a century if “business as usual” continued. She is also well noted for her book ‘Thinking in Systems’ [20] published posthumously in 2008. Thinking in Systems is an excellent beginner’s resource for what is still a relatively nascent but incredibly powerful discipline and approach, and one that I will reference throughout as we begin to uncover the universal language of reality. Systems thinking has been described in many ways, from “the paradigm of foresight” [21], to perhaps a resolution to the proposed “root crisis of humanity” concerning how we think [22]. While you may be sceptical that there is indeed a root problem that births all others, systems thinking has seen increasing use across widely-differing disciplines in the social, life, and physical sciences. That is to say, systems thinking has been shown to be useful for tacking many unrelated problems. To understand why, we will begin by exploring the history of the discipline.

Aristotle believed that knowledge should be deductive, as outlined in his canonical texts that formed the basis for studying the natural world in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. Among his teachings was teleology; every object out there in reality had a goal that it was working towards, determined by said object’s intrinsic character. An acorn grew into an oak tree, and a stone fell to the floor, because it was in the nature of acorns and stones to do so. If you had attended perhaps your own university back then, you’d have been taught that not only did God pre-define every object’s intrinsic nature, but he also pre-defined every object’s symbolic nature. As an example, the pelican was believed to feed its young with blood from its own breast, and so humans studying the natural world through Aristotle’s teachings believed that the pelican existed the way it did partly as a symbol of the self-sacrifice made by Christ [3]. From the 16th century onwards, the shift gradually occurred from Aristotelian methods, to studying phenomena as we found them and inferring general principles, which we call the ‘birth of science’. Gradually must be emphasised; to challenge Aristotelian teachings meant to rebuild our understanding of reality from the ground up, which was a very tall and unpopular task. In fact, it was not until 1572 that Aristotle’s science could be proven wrong by direct experience, when a stellar supernova was observed to light up the sky with a new star, undermining the tenet that ‘the heavens never change’ — nevertheless, Aristotelian thought dominated university curricula until the mid-1700s.

The emphasis on literal interpretation grew stronger in the proceeding periods, perhaps most famously characterised by Martin Luther. Indeed, as the church gradually lost its battle with scientific doctrine over the purported sinfulness of intrigue, we began to wonder about physical phenomena, their origin, their function, and their dynamical relationships — the world was evidently a grand, coherent, interlocking system. While the church pivoted to pointing to the many grand systems as expressions of divine design and creation, the scientific study of these systems and how they evolved over time continued on at increasing pace. During the Enlightenment period, people began to talk of ‘economies’; intricate networks of interrelated, functional parts. There was an acknowledgment that ‘out there’ in reality, many various interdependencies could be defined between different things, with God typically believed to be the orchestrator. In 1633, describing the phenomena of the world, George Herbert [4] wrote “each part may call even the furthest from itself [by the name of] brother”, and this echoes in our contemporary understanding; we know that any two physical phenomena share the same medium of spacetime, and hence have a relationship to each other.

‘Systems’ can be defined as sets of things (we can hark to concepts from Set Theory in mathematics) which work together in an interconnecting network. Everything in this universe is a system, and this should not be too controversial a statement — it perhaps might be enlightening when you stop and consider it. Subjects in reality are what they are, and ‘systems’ are a human-made signifier. By virtue of the fact that everything in this universe shares the same medium, and hence has at the very least that fact in common, the human mind is capable of signifying in this way with comprehensive application. Arbitrarily draw the lines anywhere your eyes gaze, and you will be able to describe various systems; whether that be the biological system that is your eyeball, the HVAC system in the room you’re in, the electronic system displaying this text; or the system of characters and grammar that comprise this manifesto. Outwards, like Russian nesting dolls, systems exist within systems, fluidly gliding through scale. We can describe systems that comprise your city, region, or society, finally culminating in the grand system that is Earth, which, through the systems perspective, we can view as a very brightly shining beacon of concentrated systems within the universe — the importance or profundity of that insight being the opinion of the reader.

But of course, the Earth is a constituent of the solar system, and so on. The official term for this aspect of their nature is ‘embedded systems’ [20]. Systems are made up of constituent elements. Those elements (the pieces of the system) are themselves systems, and they are also constituents of larger ‘parent systems’. A plant is a system, found in a ‘forest system’, subject to the whims of the local ecosystem; but, that plant is also found in the larger ‘earth system’, subject to grander whims in the climate or ozone layer. Somewhere in between these two systems, the plant can be understood as belonging to the ‘nation system’, subject to the whims of the local anti-conservationist politician.

‘Systems thinking’ itself has even had the systems approach applied to its own definition, such that ‘systems thinking’ is itself a system [25]. But before we confuse ourselves, I must make the distinction between systems thinking, and the greater discipline of systems theory. Systems thinking is a mode of conceptualisation, like an ‘operating system’ for your brain. Taking a systems perspective has been shown to be useful, because in doing so, reality becomes more clear. As we discussed in the introduction, seeing reality more clearly allows you to bend it to your will more easily, and hence it is a useful new skill to acquire in the present. However, this ‘seeing reality’ does not happen automatically with no effort. To emphasise the human-constructed nature of systems, consider any three items in the universe, for example: the unopened energy drink on my desk; the Voyager 1 satellite; and a stone untouched by man at the base of Mount Rainer. By considering these items, they now exist in a system. What can this system do? Very little. The objects that belong to this system are in no way materially connected outside of the conceptualisation of their connection in the reader’s mind, and hence their physical behaviour through time does not change at the behest of this system. It is a conceptual system of signifiers connected by your consideration of them together. This system does little, but it could now be said to blink in and out of existence with each reader of this passage, going on to effect their understanding, and perhaps their actions. Anything can be a system, but some systems could be said to ‘exist’ more than others. My example is very arbitrary, and indeed, Meadows gives the following definition for systems:

· “A system isn’t just any collection of things. A system is an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organised in a way that achieves something” [20].

This could be said to exclude my own example. Outside of my own mind, the three stated objects share no interconnections, they are indeed just a collection of things. However, insofar as I have brought them together for the readers’ consideration and learning, perhaps the system does achieve something, despite the geographical separation of the elements involved. It is not physical proximity that makes or breaks whether something is a system, as shown in another quote by Meadows:

· “Is there anything that is not a system? Yes! A conglomeration of elements without any particular interconnection or function. Sand scattered on a road by happenstance is not itself a system. You can add sand, or take away sand, and you still have just sand on the road” [20].

But yet, we could argue that a scattered pile of sand is a system. It exhibits behaviours, such as sticking together when moisture is introduced, which will go on to effect it’s behaviour if the nighttime brings about sub-zero temperatures, which will effect its physical structure when vehicles drive over it. If we happened upon this pile of firm, tire-tracked sand in the road, and wanted to understand why it looked and physically behaved the way it did, we would have to appeal to its ‘elements’, or pieces: the sand, water, and ice particles, along with their relationships to each other. But what we have actually done here is taken the reductionist approach: we have broken down the pieces, and have considered their workings to derive information about the larger structure. Even though we can adopt the systems terminology and give our enquiry a false air of systems, essentially all we have done is applied reductionist thinking. This is the essence of the ‘human-constructed’ nature of ‘systems’. When your subjective mind looks at reality out there, it always arbitrarily draws the boundaries for the system being defined. We can call the pile of sand a ‘simple system’, elements comprised of very simple physical interconnections, such as proximity. There are no chemical reactions when it goes freezing overnight, the only ‘behaviour’ the system exhibits are physical changes. And indeed, with simple systems like this one, the outcomes in understanding when taking either the reductionist or systemic approach are indistinguishable, or ‘pseudo-systemic’.

Herein lies the core difference between the reductionist approach, and the holistic approach. The clue is in the title, holistic — real systems have a ‘wholeness’ to them. Take grains of sand from the pile, and nothing changes. Take vital organs out of a biological system such as yourself, and major changes occur. Many of these systems have integrity, and actively work to retain said integrity. And indeed, given the arbitrary human-constructed nature of any boundary we draw, when we are tasked with ‘best-defining’ a system, we can try to identify integrity manifest. We can see this everywhere we look. A cell in your body has a cell wall to protect the inner-workings, and is compromised if the cell wall breaks. Zooming out, within the bounds of your skin is the biological system that is you. The boundary between your physical body and external reality is sharp and clear, and the scope of your body’s defence mechanisms doesn’t extend beyond the skin, which is an organ that exists explicitly to protect your insides. The four walls and roof of your home have been made with each other in mind, to ensure their collective integrity, securely housing various systems inside. The nation installs infrastructure and enforces policy that is tough on illegal immigration, to protect the integrity of only the nation’s borders. However, because every system is a part of a larger system and said larger system’s whims, anywhere we find integrity, we find tension with external reality.

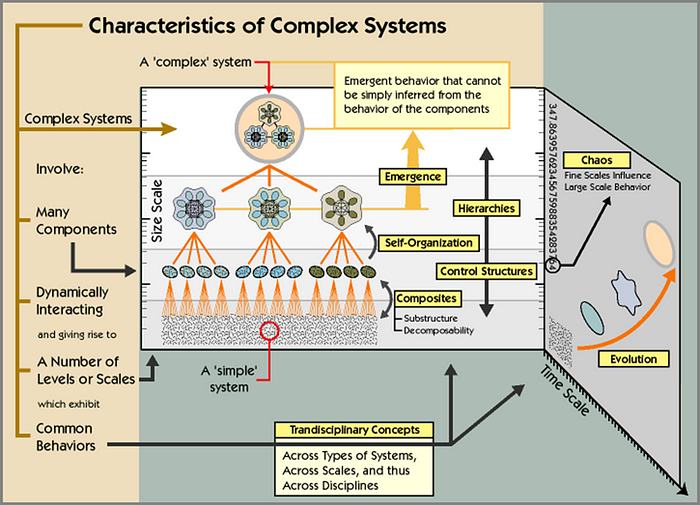

However, not all systems are equal. We have ‘simple systems’ like our pile of sand, and we also have what are called ‘complex systems’. For example, any system capable of maintaining and repairing its integrity will be a complex system. The definition of a complex system encompasses those systems which are comprised of many different elements, with many different and dynamic relationships therein. This is the definition of complexity. So many constituent pieces (elements) behaving according to the whims of their many other constituents to constantly differing degrees, which adds up into the behaviour of the parent system as a whole. That is to say, the behaviour of the complex system is the cumulative total of all behaviour occurring within its constituent elements.

This causes the behaviour of the complex system to be sporadic, dynamic, and unpredictable, while still maintaining a given level of integrity. The human body is a great example. Zoomed out, seen from across the room, a person is just a person. Zoom in a little, and we see that they are subtly moving even while still, their head slightly swaying and their hands slightly trembling. Blinking at random intervals, perhaps scratching their arm suddenly, or adjusting their leg, and so on. These behaviours are the product of many microscale developments within their body. The system is protected by an outer barrier of skin, many layers of dead cells that are constantly flowing towards the very top layer, before falling off flying away as household dust. When we cut ourselves on something, we see how blood cells flow to the site of injury, and then clump together to close up the cut and prevent further blood loss. This happens automatically, our subjective will is not factored into the equation. At the same time, we sporadically fall ill, perhaps even gravely ill. One person smokes their whole life and survives into old age, dying of other causes, while another person dies of aggressive cancer having never smoked or drunk in their life. There are countless billions of biological mechanisms at play that build up over time into such a result, your body replaces 330 billion of your cells (or 1% of the total) every single day. A reductionist approach to biology has been instrumental to the birth of modern medicine, and continues on into the depths of quantum biology and the theoretical. But there are many health problems on the human scale that are the product of ambiguous and conflicting pathologies, and this is the nature of our difficulties in the present day: combatting the idiosyncratic nature of ill health, while using limited resources, and a relatively slow development time.

Of course, systems are human constructs, as are things like ‘predictability’; complex systems behave with a given level of ‘unpredictability’, which is directly correlated to our present understanding. Meadows and others in the field believe that there is no competition between reductionist and holistic thinking — instead, they are complementary. A key dynamic of human existence is that virtually all the systems found out there in reality on our observed ‘macroscale’, our daily lives, are best described as complex systems. Of important note is that the bigger a system is, the wider you arbitrarily draw the boundaries of the system to be defined and studied, the more systems there are within, and hence the more unpredictable the properties and behaviours of the system will be over time. This why we are having to confront increasingly new and large problems, as systems such as nations, economies, and communities grow larger and more advanced, with more factors to be considered and more initiatives to be taken.

The war against complexity in all facets of life often takes place in the literature. The academic disciplines grow larger with materials, ideas, and practitioners over time; the express purpose of their existence is to bring control to the large systems of the world through understanding their function, and this could be said to be the least controversial definition for ‘progress’. In this way, we can see that not all ‘metaphysical systems’ are baseless theories, or superstitious nuisances to be swept away. As visualised above in Figure 4, all observable phenomena in the universe originates from the behaviour of the physical substrate (particles) over time, and as we progress upwards through scale and observe these higher-level behaviours (unexhibited in the constituent parts), humans create metaphysical systems to make sense of its function on said scale. They are not the physical system in question, but rather a representation in the form of signifiers that grows increasingly vivid over time with the study of the field by humans. These are known as the disciplines, or ‘bodies of study’ directly related to a given ‘phenomenon’ — or ‘system’, which we can use interchangeably, as all ‘phenomena’ in reality are systems, and elements of larger systems. The disciplines are themselves systems, made up of physical objects such as books and papers in university libraries, along with mental objects, which is where it earns the name of ‘metaphysical’ system; the thoughts and recall of those who have read the literature on the discipline. This system has certain behaviours; researchers in the field coalesce and conduct experiments using more physical equipment, from a discussion in a dorm room, to all day in a wet laboratory.

This leads us onto a novel property of complex systems: emergence. This describes how complex systems, as a whole, take on properties that the constituent pieces that comprise the system do not have, in ways that cannot be easily inferred. The concept of emergence similarly has its origins in Aristotelian science; however, emergence has lacked behind its teleology and symbolism counterparts in terms of scientific unmasking. If the reader is knowledgeable in the philosophy of science, they may have preconceived notions about the concept, particularly that it is pseudoscientific; for if we imagine things as more than the sum of their parts, in doing so, we are making an appeal to ‘mysterious additions’, and hence this would be an unscientific, metaphysical appeal. Indeed, emergence is prone to being conceptualised too abstractly, even with effort to not do so.

This trickiness of emergence is an important problem. One reason why is that ideas born from the inner-world of your mind are capable of manifesting over time into phenomena in reality. We do this every day. I am doing it now as my inner voice becomes words on the screen in front of me, now forever ‘out there’ at least once in reality. All of us weave our narrative into the physical universe through our actions, many of which begin as thoughts in the mind. This is a form of emergence, from a mental object to a physical one, whether that be your unique (though too-often ineffective) paper airplane design, a piece of art that takes years to produce, or your dinner. Very similarly, if you are an entrepreneur, or if you seek to change the world, or otherwise bend reality to your will in a way that brings you happiness or success, if you do prove to be successful in decades’ time, it will be because your vision of the future has manifested through your actions, and your control over various systems. To be successful, the nature of emergence must be well understood and considered. I believe the systems perspective as a way of thinking is uniquely designed to facilitates this.

Attempting to ground emergence in physical reality, Derek Cabrera [2] argues that no tenet of reductionism inherently implies or explicitly states that the parts of a system must be material objects, and as such, the inclusion of immaterial objects, such as dynamical relationships, structure, organisation, and any other intangible element is valid. If we are to factor in all immaterial properties of a system as valid parts of said system, then during the emergence of a new property, no addition or metaphysical appeal needs to be made — rather, different pre-existing metrics change. However, depending on your view, the casual addition of immaterial properties as valid parts of a system may not be appealing upon first consideration. Indeed, by virtue of its philosophy-of-science roots, thinking about systems can quickly become confusing if you aren’t consistent in your thought-processes; there’s more than one foundation to rest your house of cards on when considering systems, but trying to introduce multiple foundations is bound to cause a topple.

Herein lies the essence of why collaborating on systems is difficult, and why despite great effort from the community, the adoption of the framework has been gradual, with varying real-world success. To exemplify this difficulty, let us examine two examples of emergence:

- (1) Societies wage war. ‘Society’ is a system, partly comprised of humans. An individual human cannot wage war.

When trying to wrap our heads around this example of emergence, some people will resolve to consider the real-world pieces that comprise war, such as the material pieces, and the logistics. Others may instead consider, or more highly weigh the importance of, the anger found in man, and how war ultimately originates from it.

We can take these opposing views to the extreme with our second example:

- (2) Water is wet, but H₂O is not.

The coherence in causality between scale seems to break down for water being wet. H₂O couldn’t possibly be ‘wet’, for it is comprised — in part — of a particle, the electron, which has no spatial dimensions, meaning no matter how you would wish to imagine what ‘wetness’ is analogous to on this scale, the electron is incapable of acting as an analogue without an appeal to metaphysics. And indeed, if you had built your consideration for the emergent property of water being wet on a more idealist foundation, if you are a religious individual, or a believer of the supernatural, you may be more inclined to appeal to metaphysics, believing that the answer is a mystery, or beyond human understanding, or obscured by incorrect physics — and indeed, idealist reasoning has been the default mode of thinking for most of the humans who have ever existed. If however you instead considered it from a materialist foundation, an empiricist considering wetness would likely argue that wetness describes how H₂O ‘permeates a surface’, the atom’s size and it’s dynamical relationship to other atoms is the determinant factor of whether something on the macro-scale is wet, and so on.

Upwards through scale, systems combine into larger systems with new emergent properties. But this doesn’t stop at the human scale. Systems continue to combine and grow into huge systems, capturing humans inside them. The reader, the author, and everyone else belongs to various systems that are larger than ourselves, such as your city, or the economy. These systems share similarities with any other system; they are comprised of a group of smaller pieces, which for large systems include multiple humans. Each of these pieces are connected in different ways, and all of these pieces behave in certain ways according to what I will call the ‘reason of the system’, like a rulebook for all the pieces. You belong to certain large systems, and you operate within these systems, making up part of the ‘behaviour’ of said system. You do this largely unconsciously.

As an example, imagine you are returning home from work in your car. You approach a junction as the traffic light turns red, and you hence slow to a stop in front of another car. We can understand this road junction as a system, comprised of roadway, traffic lights, physical barriers, cars, and of course humans, whether they be pedestrians, or drivers. You have unconsciously entered into this system, and you begin to behave in a certain way as a result. An alien observing the junction from above, while completely ignorant of what the junction is and why it exists, can recognise it as a system with pieces and behaviours. Upon further study, still oblivious to the meaning of the system, they could begin to trace and agree collectively on connections within the system, such as a green light corresponding to the movement of certain objects in the system that are always within the bounds of the physical barriers — these metal guardrails and pedestrian infrastructure are themselves pieces of the system that seem to change less often from the aliens’ perspective.

For the first time of many throughout the next few chapters, for explanative purposes, I will draw a parallel to a different phenomenon in reality. Imagine an atom, comprised of a nucleus, and a few electrons orbiting. A stray photon of light from elsewhere flies nearby, and collides with the atom. If you appeal to Bohr’s interpretation of atoms, you may imagine a system similar to our solar system, with the planets orbiting around the sun. This is a valid enough comparison, but there are key differences. The electron orbits the nucleus due to the electrostatic force instead of gravity; also, the orbit of the electron is said to be ‘quantized’. This describes how electrons orbit at fixed distances from the nucleus, unlike planets which orbit at any random distance. As our example photon crashes into the atom, the photon’s energy is absorbed into the atom, which causes an incumbent electron to move into a new fixed orbit, a different but specific distance from the nucleus. The electrons are unconscious, but nevertheless enter into ‘systems’ and behave in very certain ways. Similarly, we enter into ‘systems’ ourselves and behave in very certain ways, regardless of how conscious we are of this reality. This unconscious behaviour I have described is the expression of a more fundamental reality: that of all observed phenomena in reality developing through time. When any event happens in front of us, important or otherwise, before we consider the event and it’s meaning; before we consider the historical context of the event; before we consider the cultural paradigm or value of the event; before we consider our religious beliefs, before we ask ourselves any of the deepest questions, at a more fundamental point before we consider any of this, we can understand the event as purely the development of a system through time, according to the behaviour of the elements that comprise it, subject to the whims of its parent systems.

The design of large systems and how they influence people is covered by a few different disciplines, including the relatively nascent but now flourishing field of behavioural economics. Herein, the power of the systems perspective can be grasped. Let us imagine a supermarket. Strip away everything about the supermarket, and consider it as nothing more than a system. The purpose of its existence is ultimately to generate money. To achieve this purpose, it must entice in humans who possess the money to be extracted. Next, consider the physical parts of this system: the bricks, mortar, the items for sale, and the aisles that arrange them. Because they are physical objects, we are capable of arranging them in differing ways within the physical bounds of the system (the walls of the building). Through the acquisition of knowledge within the realm of psychology and behavioural economics, this system is often strategically calibrated to maximise money being extracted from visitors (which are in real terms newly introduced and fleeting pieces of the system). An example of this calibration is how supermarkets position the fruit and vegetable aisles at the front of the shop. By setting a tone of freshness and bright colours gifted by nature, those entering the store are said to have their moods heightened, as well as their hunger triggered, which could influence purchase decisions in ways advantageous to the store.

Our safety and livelihoods depend on many various systems, most of which are growing increasingly incomprehensible to us presently, with some complex systems trending towards being unfathomable in both directions of scale. And as mentioned, emergence doesn’t end at the macro scale; when we create systems that are larger than ourselves, emergent properties on that scale can manifest, which translates abstractly into different human experiences. As shown in example (2), disagreement on systems can begin, psychologically speaking, immediately. Those who don’t venture to the depths of reality, or who have not learnt, or care to learn the philosophy of science, leave their reasoning to be primarily driven by their subconscious, and emotions. This renders the motivations driving their reasoning behind solving systemic issues as likely confused, incoherent, or misinformed, no matter how technically or narratively fluent explanations may be. While we will of course not have to consider metaphysics for many systemic issues, the example aims to highlight how likely humans are to clash when trying to solve systemic issues in the modern day, especially ones that are complex and multi-faceted. The boundaries we use to define systems are always arbitrary, and an invisible figment of our personal imagination; the picture we hold in our minds of a given large and complex system is poorly understood even to ourselves. When two people debate a system, even if they are both distinguished in their knowledge of that system, particularly for systems larger than the macroscale, their idea of that system is always bound to differ through no fault of their own, as we subconsciously differ in our definitions of constituent parts, their importance, function, the influence of other connected systems, and more.

Indeed, systems larger than ourselves dictate our lives deliberately, and accidentally. Returning to the period that arguably birthed Systems Thinking, as Aristotle and the church lost their grip on authority of reality out there, we also saw the birth of a system that has likely played the most prevalent role in influencing our lives: Capitalism. If you were born into the 18th century and before, you would’ve likely relied on tilling the lands for your survival, doing so in ways that had been passed down since the unknown dawn of time, perhaps also believing that to even imagine doing things another way was sinful. Peasants tilled the lands in order to ensure their reproduction, and any surplus labour beyond what was required for survival was appropriated by a class of individuals who, by virtue of access to military, political, religious, or other recognised authority, were in a position to exercise direct coercion. By Adam Smith’s time, some peasants recognised in themselves, as affirmed by the state, a freedom to offer their labour elsewhere, unlike the slaves or serfs of before (and after). These peasants did not own any land to provide for themselves; they were propertyless, and could only access the means to even exercise their labour by offering their labour for a wage. This mode of ensuring human reproduction, and hence perpetuating the system that we call ‘civilisation’, meant that a Capitalist state could appropriate surplus labour without the need for direct coercion — instead doing so by purely economic means.

Markets have been around since the dawn of time, as humans have always sort to barter their surplus labour for other needed material items. But the unprecedented difference between those markets and the Capitalist market was the concept of ‘commoditisation’; virtually everything in a Capitalist environment can be understood as a ‘commodity’ that could be sold by the market for its determined worth. Those working the land relied on the market to sell their labour power, and Capitalists relied on the market to find and buy said labour power, as well as the means of production — not only that, but Capitalists further relied on the market to sell surplus labour as a commodity for profit. Whether a labourer, or an appropriator of labour, humanity now relied on the invisible system of the market for its continued self-reproduction. And thus, the market has become a central dynamic of human existence, as well as an unprecedented complete departure from the social forms that dominated history before this point. In doing so, humanity relinquished a form of control to the so-called ‘invisible hand’ of market forces [5]. This was first seen in England, set forth by the invading Normans in the 11th century, who brought with them advanced administration which, accompanied by other factors such as a relatively early-on demilitarised English aristocracy ( when compared to troublesome regional powers seen on the Continent ) led to a centralising effect that created fertile ground for the first national market. This departure cannot be understated; only in the Capitalist system, regulated unconsciously by the market, did labourers and appropriators suddenly find themselves having to compete with others to secure the means of production, a buyer for their labour, or a buyer for their surplus.

We unknowingly found ourselves in a ‘human system’ ( defined as a system comprised of more than one human ), comprised of rules, customs, and subsequent behaviours, which we call the market. When humans gave up control to the market in this way, the system birthed competition, an emergent phenomena manifested in the human condition. And consequently, the need for things to constantly change, improve, and compete also emerged. This stands as a great example of humans entering into systems bigger than themselves, largely unconsciously. Smith didn’t ‘invent Capitalism’ more than he observed its nature out there. This came at a time when humanity had warmed to the idea of ‘natural economies’ of physical phenomena, ( detailed extensively by Newton in the Principia ), and hence sought to describe human life through similar concrete mathematical laws and principles.

Humans find themselves constantly and unconsciously entering into systems. This may be for a short period, such as navigating an intersection managed by traffic lights; or, it may be long term, such as our career path according to the capitalist system. We are not typically conscious of this dynamic of existence. As physical beings, there is a direct similarity between how atomic structures unconsciously enter into marvellous systems larger than themselves, and how humans do the same on our own scale. Indeed, the universality of applied Systems Thinking is useful for coherently understanding our complex world.

Systems Thinking is a powerful tool, and we invite the reader to utilise it to the best of their ability as we progress throughout these essays on reality.